Kate Bosworth, that is. The lead actress in the surf movie "Blue Crush." Or more particularly her character, Anne Marie Chadwick, a Hawaiian girl from the wrong side of the island who lives to surf but pays the rent for herself and her little sister by working as a hotel maid and teaching tourists to surf.

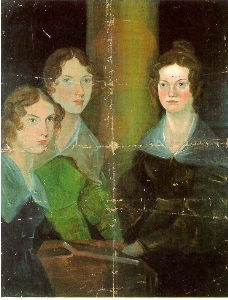

Struggling for money was something with which the Bronte sisters were more than familiar. What, after all, were their life choices pre-1850 except servitude as governesses, deepening poverty if they stayed home as unmarried women, or marriage to any man likely to keep a roof over their heads and food on the table? Yet all three of the surviving Bronte sisters, Charlotte, Emily and Anne, escaped their cheerless existence by exercising their imaginations and their intelligence, writing novels and poetry.

From left to right: Anne, Emily, and Charlotte This picture of the three Bronte sisters was painted by Branwell Bronte. He had painted himself into the picture, but painted himself out later. There is still an outline of his form in the pillar.

Occupying my thoughts today are the overlaps and divergences between Charlotte's novel and Emily's, and the persistence of their themes into the present day.

In 'Jane Eyre', Charlotte Bronte wrote of the life of a governess and schoolteacher. She wrote what she knew - a harsh girls' school and harsher religious teachings, followed by teaching and governess jobs - but added to Jane a spirit of independence and pride that the girl's upbringing, unlike Charlotte's, would not have fostered. Add in a yearning to travel, to see the world beyond the confines of either the school or the secluded manor at which she is governess, and you have the seeds of a modern young woman's dreams, albeit without much opportunity to fulfill them (except by a good marriage).

Emily Bronte wrote of a young woman more at home on the wild moors than in polite company, and endowed her with a fond father who let her run wild in ways that sheltered, slightly fragile Emily (with two older sisters already dead of illnesses in childhood) could never have pursued. Catherine Earnshaw wants nothing that is not available within a few miles around her home.

Emily and Charlotte's mother died young, leaving her surviving children with only the vaguest memories of her. Jane Eyre and Catherine Earnshaw lost their mothers at an early age. Jane finds her way as Charlotte did, pouring out her intellect and spirit on other people's children. Emily's heroines have no such solace; they are bereft of mother-love almost at birth and brought up surrounded by men, much as Emily was, living at home with her father and brother while her more resilient sisters were out earning their bread.

The heroes - or perhaps the male leads is a better term, to avoid arguments over whether Edgar or Heathcliff is the more heroic in "Wuthering Heights" - are similar: masterful men capable of schooling their horses and their women, neither capable of seeing the world through anyone else's eyes. Where Mr. Rochester is softened by Jane, Heathcliff is hardened by Catherine. One is saved by love, the other damned by it.

Breaking no new scholarly ground here, the choices their heroines make 'for love' are a marked point of divergence. Jane Eyre falls in love with Mr. Rochester because he values her mind and her conversation. Although she leaves him rather than compromise her moral values, she comes back to him as his equal, not as a servant to be elevated by marriage. Catherine loves Heathcliff with a passion beyond reason, based on physical chemistry and certainly not for his intellectual attainments or his respect for hers. She marries Linton not for love but for lack of alternatives, and soon withers, leaving behind her own motherless daughter to the same narrow life in the same small space.

Divergent choices: Charlotte's heroine crying out to be valued as a thinking individual and unwilling to settle for less than a full partnership in marriage, Emily's heroine caught up in passions too strong for her untutored rational side and coming to a tragic end that has enduring tragic consequences for the rest of her family.

(Might I insert here a plaint about the movies made of those novels? While the recent Masterpiece Theatre adaptation of Wuthering Heights makes better sense of the psychology of the characters than did the torrid 1970's version I first saw in a cinema, there is still not much effort to explore the social or cultural themes underpinning the novel. It is presented as a tragic love story with a faintly optimistic ending. All the Jane Eyre adaptations I've seen, and they have been many, have focused too exclusively on the relationship aspects, overlooking or minimizing the social conditions of Jane's - Charlotte's - upbringing/education and especially failing to explore her expressed desire for equality in life and love. She is presented always as a woman of her time and station, only slightly more outspoken than normal for those circumstances. When will we see a truly human Jane Eyre?)

And so down the century-and-a-bit to Anne Marie Chadwick, bikini-wearing surfer girl in "Blue Crush".

What, you may well ask, links her to the Bronte sisters' heroines?

Mothers dying in childbed, or being absent early in their children's lives from other causes, were not uncommon occurrences in the 1800's. That is not the case in today's England, with improved maternal health and health care generally.

Nor in Hawaii, where Anne Marie and her younger sister are nonetheless motherless, their mother having gone off with some man to California with apparently no intention of returning to take up her parental responsibilities again. Anne Marie, having left school early, is working at a menial job to keep food on the table for her little sister, trying to keep her sister in school and out of trouble.

Our surfer girl has a chance to carve out her own life if she overcomes her fears and manages to win a surfing competition that will lead to sponsorships, self-respect, and financial freedom. But a handsome man is offering her a vision of a life of ease. In modern movie romance, 'Mr. Rochester' is represented by a pro football player who hires our heroine to teach him to surf. He soon is buying her clothes and encouraging her to spend his money in the luxurious hotel suite she was employed to clean until a few days earlier. The other football players all have kept women with them, women whose clear goal is to lure as much money, jewelery and physical enhancements out of their companions as possible before moving on to another free-spending athlete.

While this modern Rochester does not hint that he himself will take Anne Marie away from her life of drudgery and poverty at the end of his Hawaiian vacation, we would have to be living under rocks not to see that she could have an easy life if she abandoned her sister's upbringing and her surfing aspirations to cash in on the succession of rich athletes and other male guests at the resorts.

Jane Eyre's moral test was whether to become Rochester's mistress instead of his wife, and Cathy's challenge is to change the life she inherited from her passionate but unwise mother. Anne Marie's great moral test is whether she will repeat her mother's life choice of running out on her family responsibility and, equally important, turn her back on her own goals in favour of an easy escape from her present poverty. Will she be a Catherine or a Jane?

The night before that surfing competition, she faces the truth of what she wants in her life: enough money to pay the bills, her mother to come home, her sister to grow up without any disasters, and to win the surfing competition for herself. The only one of those her Mr. Rochester can provide is money, and that, by the nature of their relationship, is a temporary fix. Winning the surfing competition will provide two out of the four and increase her sister's chances of breaking out of the family pattern in her turn. She leaves him and goes home to prepare for the competition.

As Jane Eyre is rewarded for her virtue and high principles by gaining not only an inherited fortune of her own but an equal love with Mr. Rochester at the end of the novel, so, at the end of the movie, do we see Anne Marie rewarded. She overcomes her own fears to give the best athletic performance of which she is capable, earning her a sponsorship and the promise of not only income but support for continued training. Her other reward, very like Jane's, is to be treated as an equal by her modern-day Rochester, as a fellow athlete with a career of her own rather than as the servant girl he can (however temporarily) lift from her poverty.

As Jane Eyre ended on the happy note of her marriage to and children with the man she loved - the ultimate reward for women in Charlotte Bronte's time just as Catherine Earnshaw's fate was the ultimate punishment for women who dared to love both deeply and unwisely - so Anne Marie Chadwick's movie tale ends on the happy modern note of rising career promise, improved income potential, and a future that includes her Mr. Rochester as a boyfriend who will understand the demands of her career and support her efforts.

And this, at bottom, is why Jane Eyre is still being read, taught, and re-visioned in books and movies for young women more than 150 years after Charlotte Bronte wrote it. We women may have come a long way, baby, but we still struggle with the need to be independent, to find our own financial security and to balance our career advancement with our relationship needs.

What does Wuthering Heights tell the modern woman? That's a story for another day, and I'm not sure I can think of a movie that makes a parallel.